Argument structure

Relevant Publications

- Wolpert M, Ao J, Zhang H, Baum S, Steinhauer K, 2024 | The child the apple eats – processing of argument structure in Mandarin verb-final sentences

Relations between verbs and their arguments are the foundation of sentence structure, and languages vary extensively in how these relations are expressed. English, for instance, relies almost entirely on word order to communicate agent and patient roles, and word order will generally “win” over other cues for interpretation in the case of ambiguity or competition with other cues.

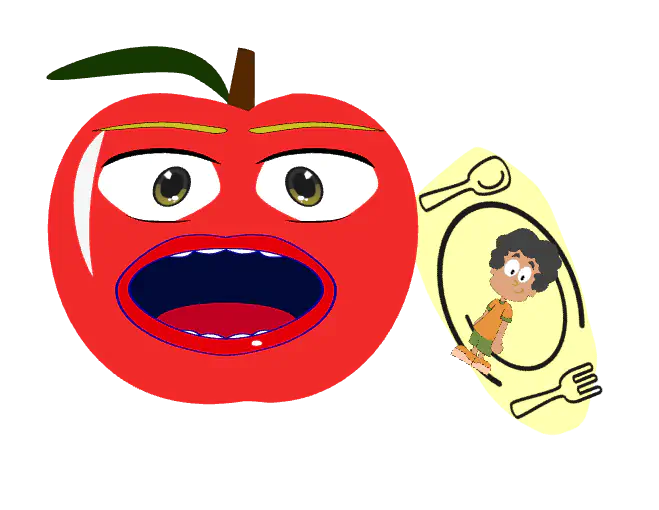

We can test cue competition by using strange sentences like “The child the apples eats.” In this sentence, the verb “eats” is inflected for 3rd-person singular and semantic knowledge contends that apples cannot eat children. However, despite the cues of verb inflection and semantic knowledge, most English speakers interpret this sentence to mean that “apples” is the noun doing the eating, merely by virtue of directly preceding the word.

What is your own interpretation of this strange sentence? If you speak a language other than English, you may be informed by cue weighting parameters of your other language(s). For instance, Mandarin allows both subject-object-verb and object-subject-verb word orders, as well as lacking inflection for subject-verb agreement. Accordingly, semantic knowledge and context drive Mandarin sentence comprehension, so Mandarin speakers often opt for the semantically appropriate agent of the verb.

To study the fundamentals of argument structure processing, we had Mandarin monolinguals read sentences with a variety of grammatical and semantic manipulations (word order, presence of coverb, agent animacy, reversibility of the semantic event) while we recorded their EEG activity. We found that there is a language-specific profile of cue weighting that is more nuanced than a simple linear ranking, and even within a language there is individual variability in sentence comprehension strategies. EEG data showed that comprehenders likely do not wait until the verb to make argument structure decisions, and sentences whose grammar violates semantic knowledge elicit a brainwave pattern consistent with models that predict crosslinguistic differences in core processing mechanisms for sentence comprehension.